We live in a time of immense institutional failure, a murky world of corporate accountability, and an era of an ever-fading sense of personal responsibility. If you want proof of how important leadership is review the excuses put forth daily by our political, business, educational, and sports leaders. Watch how they gloss over mistakes, find a scapegoat, spin the truth, or simply lie.

Good leadership is a matter of character. Effective leadership hinges on trust and is cultivated in the words and deeds of leaders. Dishonesty and artificiality are incompatible with honorable leadership.

In a complex world with an endless array of problems, leadership matters.

Thoughtful leaders, those that can transform people, communities, and organizations take ownership of their role and responsibilities. Success and failure are always part and parcel of any team endeavor. What separates the great leaders from the average is how they respond to and handle adversity and failure.

Exemplary leaders own their failures. Admitting ownership of one’s problems and failures brings with it the opportunity to teach others how to do better.

If a mistake has no owner it is likely to be repeated. Every disappointment can be corrected and serve as inspiration to better solutions.

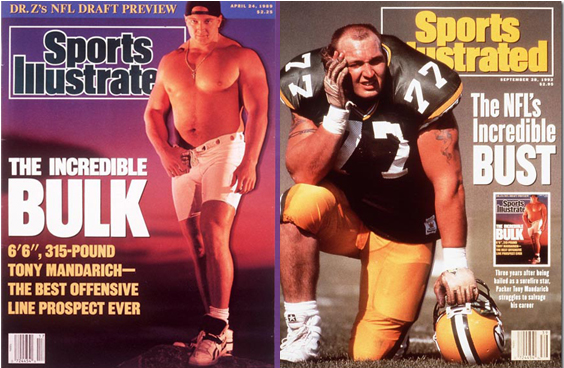

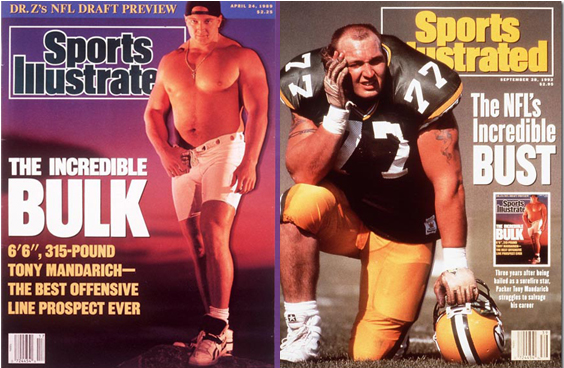

I recently sat down for a conversation about athletics, leadership and responsibility with Tony Mandarich. Mandarich was the second pick in the 1989 NFL Draft and the subject of a Sports Illustrated article that featured him on the cover. The SI cover positioned Mandarich as “The Best Offensive Line Prospect Ever.”

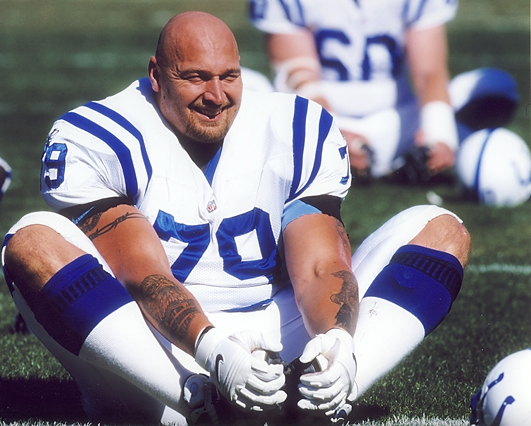

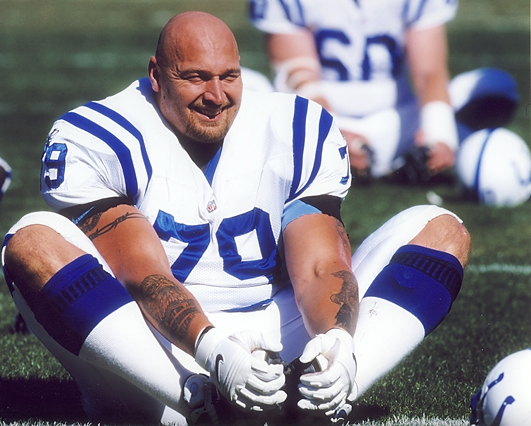

Mandarich never played in a Pro-Bowl game and the Green Bay Packers, the team that drafted him, let him go after his contract ended. In fact, today when the draft gurus talk about the greatest busts in NFL draft history, it doesn’t take long until they get to Tony Mandarich. However, unlike the other busts he’s grouped with, Mandarich has personified growth and development through discipline and self-leadership.

In his book, My Dirty Little Secrets: Steroids, Alcohol & God, Mandarich reflects on his career in Green Bay as “the beginning of four years of shame, embarrassment and disgrace…I was so constantly doped up by drugs that the reality of the humiliation didn’t hit until much later, when the drugs were finally wiped out of my system.”

Mandarich, who admits to steroid use during his college years, found himself in the NFL with the responsibility—self-imposed and media driven—to live up to his billing as the greatest prospect ever.

I asked Mandarich, a two-time All-American at Michigan State what kind of leader he was and what kind of leader he was willing to follow during his playing career.

“I felt I was a leader. I led by example. I did what I felt was above and beyond the call of duty.

I didn’t want average results. If you want average results, you do average things. If you want greater results, you have to go beyond what’s asked of you. And I felt that I did. I feel I do that today in my business.”

An effective leader knows the capacities of each team member. Knowing each others’ strengths and weaknesses is vital to maximizing a team’s potential. “I guess I’ve always been blessed with the understanding that no one person has all the answers and I applied that to myself,” Mandarich said regarding team leadership.

“I led more by example, though at times if I saw something that was wrong or going to become a cancer, I addressed it right away.”

As for leaders he was willing to follow, Mandarich stated clearly that “Mostly guys that led by example. There w[ere] a lot of talkers but not a lot of walkers.”

“Guys that led by example were way more impressive to me. Some of those guys were also vocal, but not in a screaming kind of a way.”

During the course of our conversation it became obvious that Mandarich has become a very humble man willing to share his story knowing that it can have a positive effect on people. This wasn’t always the case. As a media created superhero, Mandarich soaked in all the hype and the fame that came along with it. He was one of the first rock-star rookies.

Leadership is a fundamental aspect of organizational life.

Today we see professional athletes quick to shift blame and refuse to take responsibility for their actions. Mandarich, too has noticed an uptick in athletes avoiding responsibility and accountability. Mandarich’s book is counter to the sport culture—he actually takes responsibility for his struggles, for his failures.

In taking ownership of his failures, Mandarich states, “I was the problem. It wasn’t the organization or that geographical location. Wherever I was, I was the problem until I chose to change it.”

“How you live, how you act on a day-to-day basis becomes your character. If you were to do your research and look at my character before 1995 and look at my character after 1995, you’d see a huge difference. A 180 degree turn.”

A crucial part of a sport team reaching its potential is the leadership provided from team captains and team leaders. Mandarich feels many college athletes may resist leading because of fear. “I think fear may be part of it, also, ability.”

The nature of competitive athletics is in many ways like white-water rafting. A season consists of periods of calm interspersed with sudden frenetic confusion and disorder. Responsibility, accountability, reliability, dependability, and trustworthiness are a part of the world of athletics. Each is a vital component of effective leadership.

“There’s no way of getting around it,” Mandarich said. “You either take responsibility now or later. It’s guaranteed you’re going to have to take responsibility. I’m of the school that I’d much rather deal with it now.”

Mandarich’s experience reinforced the notion that teams that maximize their potential do things differently than those that underachieve.

“Each year the dynamic (team) was different. How we held each other accountable and responsible. The year we went to the Rose Bowl we were extremely accountable to each other. Whether it was film study, weight room, assignments on the field”

“You miss a block on Tuesday and you’re like 'Okay, I’ll get it.' You miss the same block on Wednesday and the guy next to you say’s something. That kind of stuff—when your peer is holding you accountable—it carries a lot of weight.”

It’s been over twenty years since Mandarich graced the cover of SI and was deified by the press. He’s changed. His story is compelling and provides insights that many young coaches and student-athletes might find relevant to their situation.

“The game of life and the game of a sport are very close," Mandarich exhorted. “Some of the greatest things that football taught me was how to deal with other people. Because you’re going to get a huge range of emotions, not only from yourself, but from your peers and teammates. You’re going to see them at their highest highs and lowest lows. When they get in trouble, how you stick together. How you fight and bleed together. How you work out together and how you sweat together. A lot of that you can take and put right into life.”