Thankfully, nowadays it’s easy to find articles in sports information publications that focus genuine attention on sticky questions about how to create a soft landing pad for pro athletes whose high-flying playing days have ended. But that conversation topic hasn’t always been so popular, though.

In fact, as easy as it has now become to join in on public dialogues about pro athletes’ career transitioning traumas, it’s just as easy to conclude that before May 2, 2012, far too few sports writers and pro teams demonstrated any authentic caring about what causes athletes’ retirement woes.

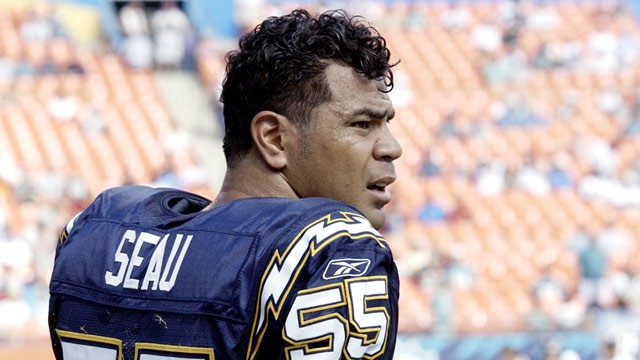

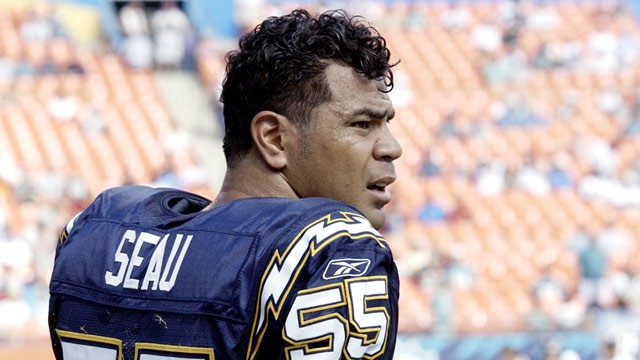

May 2 is when we found out about NFL great Junior Seau’s shocking suicide. Since that sad day, perhaps the best news relating to Seau’s death is that all of the top sports publications and most of the major pro sports leagues have been trying hard to figure out why pro athletes struggle so badly with life outside of playing their beloved sports.

For example, in ESPN NASCAR analyst Marty Smith’s May 11, 2012 ESPN.com article entitled

“How do you cope when it’s over?” renowned sports author John Feinstein was quoted as summarizing the problem faced by transitioning out of playing in the following way: “Athletes die twice.” Feinstein was referring to the shock that athletes experience once they have to leave the cocoon-like social world that they’ve been nestled in for most of their lives, and their corresponding struggles to adjust to the same life challenges faced by the rest of us.

Feinstein’s analysis definitely shows great insight into some of the core causal elements that are ultimately responsible for so many former pro athletes going broke shortly after they’ve stopped playing. And Jack Bechta, National Football Post contributor and sports agent, has taken this insight to the next level, particularly in his May 9, 2012 post entitled

“NFL is in need of a better exit plan for its players.”

In that solution-oriented piece, Bechta listed four specific action steps that he believes would help the NFL to smooth out its players’ transitions from celebrity to Average Joe status. I’ve summarized his well-justified ideas for you here:

- The league should make year-round life skills classes and programs mandatory for the first three years of a player’s career.

- The NFL should form a committee of retired players and professionals (who don’t have an axe to grind), who can help develop a transitional program out of the league and in to a stable life.

- Team owners should give retired players (who maybe played for 5 years or more) greater access to club facilities and get them involved in team activities, similar to what colleges do.

- Each team should allocate perhaps $500,000 per year towards building life skills platforms, hiring more support staff, and creating more self-actualization information resources for current players.

As you can plainly see, this conversation topic is extremely vital for the future of sports in the U.S., and we’re surely off to a good start. But those of us who’ve dedicated ourselves to helping high-profile athletes reach self-actualized status in all aspects of their lives are painfully aware that we still have many miles to go before we’ve accomplished that lofty goal.

In that light, we at Access Athletes are pleased to offer you a three-part series of columns – of which this piece, which will steer us all to a sure way to actually solve the problem, is the first installment.

Expanding high profile athletes’ identity formation

After having completed extensive research at Marquette University for his doctoral dissertation focusing on the mental and physical effects of playing pro football, one of former NFL linebacker George Koonce, Jr.’s main conclusions matches John Feinstein’s. Like Feinstein, Koonce insists that leaving a professional athletic career behind is metaphorically like dying. In fact, Koonce,

whose doctoral research was actually focused specifically on the NFL, refers to life after a player’s retirement as the “afterlife.”

The central factor that appears to have shown up in much of the research as the primary driving force behind so many former players’ post-retirement disorientation is the loss of their long-cultivated self-identities. This should come as no surprise, either. After all, let’s not forget that in this country, we shower star athletes with the kind of admiration and deference to authority that used to be reserved only for royal family members in the world’s monarchies.

What’s more, almost without fail, we heap on the honors and unwisely relax our social behavior standards for promising athletes without waiting to see if they can handle the preferential treatment. We start this barrage of pressure, coddling, and high expectations when they’re just entering their highly impressionable formative years. And we never let up until we decide that we can no longer tolerate that player’s public image.

Therefore, by the time they reach early adulthood, the only self-identity that the athletes have been consistently encouraged to cultivate is their ability to win games for their schools and developmental clubs. In other words, these remarkably gifted players have been neglectfully and forcefully steered to the mistaken conclusion that it’s okay to put all of their life skills eggs into a single basket.

This is the issue entry point through which the recent articles have launched their exploratory analyses of how to help athletes to prepare more effectively for the inevitable identity shifts that they’ll all face. And I’m pleased to say that the identity formation process is exactly the topic to which our attention needs to be directed.

On the other hand, however, the conversation about this vital element of our sports is still in its infancy. As is usually the case with important public problem-solving discussions, the focus of our current topic is on making institutional changes designed to encourage players to behave differently. Bechta’s four NFL institutional policy change suggestions most clearly and concisely represent that emphasis.

As promising as it has been that some of us have pinpointed the struggling athletes’ core psychological stumbling blocks, though, the real solution to this athletes’ career-transitioning problem is to teach them how to control their own destinies. It’s certainly a step in the right direction to focus on the death-like experience of athletic retirement, but merely discovering the issue of one-dimensional self-identity isn’t nearly enough. Even when we factor in coming from poverty into money along with being coddled from an early age as major contributors to the explanation of poor decision-making behaviors, it’s still not enough.

So here’s what we all urgently need to understand next in order to actually solve the problem. After having studied the information about player retirement, I’ve concluded that the core causal element that drives immature athlete decision-making is the choice to put all of their self-identity eggs in one playing basket, as I mentioned above. Logically, therefore, in order to solve this problem, we simply need to understand how human self-identity gets formed, and then create ways to help athletes to re-form or expand theirs.

So far, there’s been no shortage of institutional level structural adjustment proposals that have provided commercial opportunities for various firms to help players who are already interested in doing things the right way. But proposals for ways to motivate the worst behavioral offenders have been sorely lacking.

Yet the key prerequisite that can ensure the success of any serious player development initiative is to get even the more reluctant players to embrace the fact that they have the ability to appropriately apply what they’ve learned in their sports to all other areas of their lives.

The best way to improve how we utilize the teaching resources that have so far been made available to players is also frighteningly simple. At the college level (and now high school for bona fide blue chippers), and then again at the pro rookie pre-entry stage, athletes must be subjected to intensive ongoing training programs designed to show them how to view themselves in more holistic ways. Such programs must also help the athletes to develop expertise with transferring their athletic thought processes to their off-the-field challenges and obligations.

There’s actually nothing particularly complicated about transferring knowledge of one arena to that of another. After all, the thought process that creates results is the same everywhere. For example, thought plus emotional investment produces actions, and actions produce all of our circumstances, experiences, and results.

Strategic thought involves synthesizing and responding systematically to a wide range of contributing factors. Therefore, learning to think strategically about all aspects of our lives puts us in charge of our own destinies.

I submit that any athlete who is trained to view himself (or herself) as a whole person first, and only then as a highly gifted person who is able to use a highly tuned and synchronized body and mind to express living art, will also embrace strategic thinking as a way of being. Just by making these subtle mental adjustments, like Tony Gonzalez, Magic Johnson, and Ovie Mughelli have, for example, you’ll be able to experience the end of your playing days as if it were an old friend’s passing instead of your own death.

Who can provide this education for the athletes, many of whom may not yet be ready to listen without what they’d consider to be a compelling incentive? Well, it’s clear to me that forward-thinking agents, colleges, and pro teams, working closely with organizations like Access Athletes to design and implement these programs, could start a revolution of wellness and stellar citizenship in pro sports.

The good news is that this movement isn’t just beginning as a brand new thing. Some key building blocks are already in place. So in part 2 of this series, we’ll focus on Chicago-based Priority Sports & Entertainment, and how they’ve been working behind the scenes to provide their client base with educational seminars and post-athletic career opportunities.

Dr. Timothy Thompson is the VP of Educational Programs at Access Athletes. Follow him on Twitter. Send Dr. Tim a question or comment.