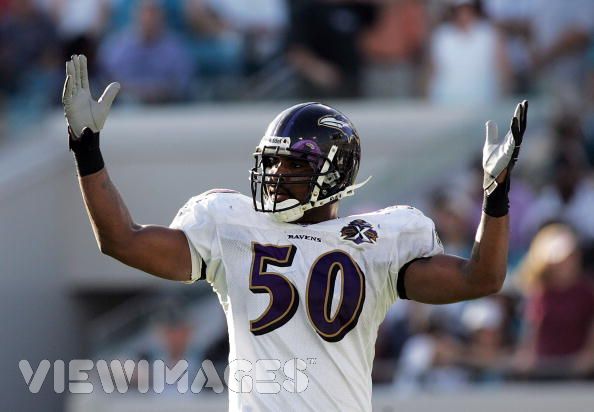

The field for Super Bowl XLIII is set and everybody is wondering if Kurt Warner can finish this improbable run and pull off the miraculous by defeating the Pittsburgh Steelers. The last time Warner played in the big game, he was at the helm for the St. Louis Rams in Super Bowl XXXVI (2002), and “The Greatest Show on Turf” came up a field goal short in pursuit of their second Lombardi Trophy since winning Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000. While the 2001-02 season marked the final season that “The Greatest Show on Turf” would ever play together, it was only the beginning for talented, rookie linebacker Tommy Polley. As a rookie, Polley started at OLB for the Rams in Super Bowl XXXVI and collected 8 tackles (6 solo) against the New England Patriots. He finished his rookie season with 67 tackles (50 solo). Polley went on to have a solid 6-year NFL career, amassing 304 tackles with 224 solo stops, and retired in 2007 after a shoulder injury sidelined him for most of the season.

I had the privilege of sitting down with Tommy Polley at his home in Owings Mills, Maryland (also my hometown) and asking him about his football career and life after football with his newly-formed company Big Vision Films.

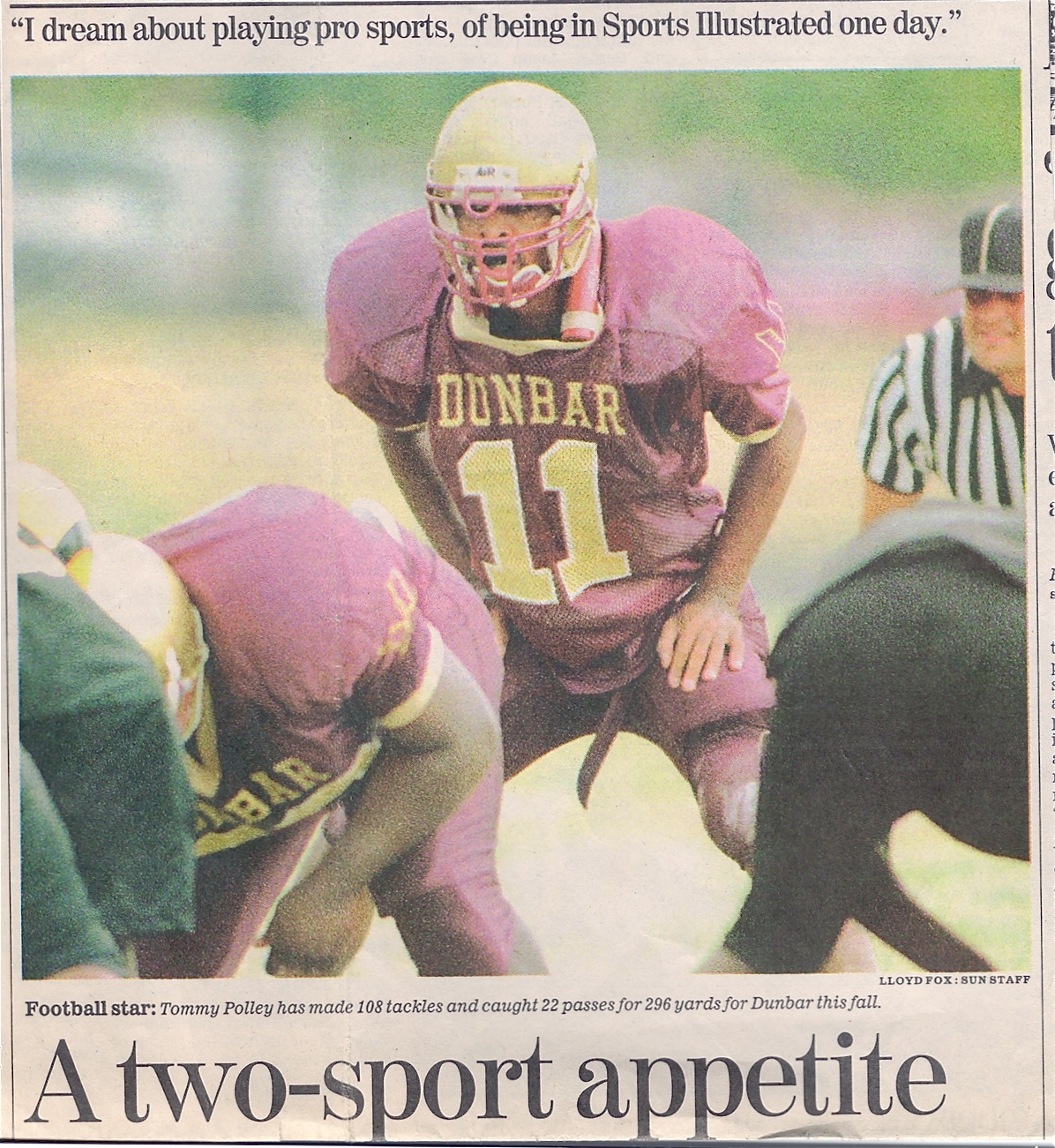

From a young age, Polley had remarkable success as an athlete. As a two-sport athlete, he was heralded as one of the top prep athletes in the nation during his senior year at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Baltimore, Maryland. In football, he was the USA Today Player-of-the-Year in Maryland after recording 208 tackles (136 solo), 16 sacks, and 8 interceptions as a senior. He was named the Baltimore area Defensive Player-of-the-Year in both his junior and senior campaigns after leading his team to back-to-back state titles.

In basketball, Polley was one of the nation’s top 60 prospects and led the fabled Dunbar basketball program—which has produced several NBA players, including Sam Cassell, Tyrone “Muggsy” Bogues, Reggie Williams, David Wingate, and Reggie Lewis—to 4-straight state titles. His senior season, he averaged 20.4 points, 10.7 rebounds, and 8.1 assists per game.

Despite being one of the nation’s top college prospects, Polley did not have much difficulty in making his final decision as to which college he would attend. “It wasn’t as bad as it’s all cracked up to be,” said Polley as he laughed. “By playing two sports, it was easy for me to cut down the list.” Polley was able to eliminate all the schools that did not have two outstanding programs in both football and basketball. That left him with Florida State University (FSU), University Southern California (USC), Syracuse, Maryland, and Florida.

What made Polley select Florida State as his top choice over the other programs that met his two-sport prerequisite?

“I just always liked Florida State. It was one of my favorite schools growing up. Derrick Brooks, Bobby Bowden…the whole Seminole chop. I just wanted to be a part of it. When I went down there, I just fell in love with the players and the atmosphere. A friend of mine went to Tallahassee Community College—Marvis “Bootsy” Thornton. (Editor’s note: Thornton would end up playing basketball for Mike Jarvis at St. John’s University.) [It] made the transition easy. I had been going down there with [Thornton] for a year. It made all the difference.”

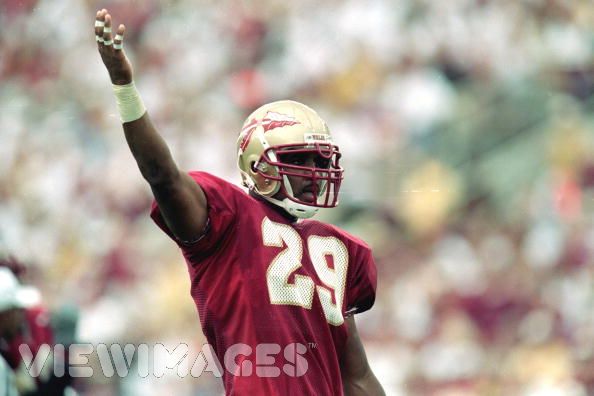

When Polley first enrolled at FSU in 1996, he played both sports. He redshirted his freshman year in football, which gave him the flexibility to walk-on the basketball team. Polley practiced with the FSU hoops team, but he decided a couple months later to focus only on football, the sport in which he felt he had the best chance to go pro. I guess following the path of Charlie Ward—becoming a star football and basketball player at FSU—was not his destiny.

The time commitment of playing both sports was not an issue for Polley; however, the basketball team’s mediocre record was too much for him to stomach.

“At Dunbar we won all the time. At Oliver Recreational Center, we won all the time. At Northwood, we won all the time. And then going to Florida State, football they used to winning all the time. So when you are used to winning all the time, your mentality is a little different. The basketball mentality was just used to mediocrity. We are going to see if we can get in the tournament. It just wasn’t my type of vibe. I’m used to winning. So, I just left the team basically and stuck to football, which was better for me anyway. [It] worked out better for me in the long run.”

Polley would become an All-American linebacker at FSU and led the defense in back-to-back BCS national championship games—2000 Sugar Bowl and 2001 Orange Bowl. He played a pivotal role in FSU’s national championship Sugar Bowl win over Virginia Tech (and Michael Vick) in 2000 after blocking a punt in the first quarter that led to a touchdown. “I had the play of the game as far as defense, but then the injury came out of nowhere,” said Polley.

Polley ended up tearing his left ACL trying to tackle Vick in the second quarter of the Sugar Bowl, and was forced to temporarily abandon his dream of entering the NFL draft and return for his senior year at FSU. “It works that way for a reason. They probably didn’t want me to leave,” as Polley chuckled.

Polley ended up tearing his left ACL trying to tackle Vick in the second quarter of the Sugar Bowl, and was forced to temporarily abandon his dream of entering the NFL draft and return for his senior year at FSU. “It works that way for a reason. They probably didn’t want me to leave,” as Polley chuckled.

He recounted the emotions that went through his mind when he suffered the injury.

“It’s over. I was thinking about leaving. So, now I got come back and go to class. That was the main thing. Then, all we going to do is lose the game. We were playing against Michael Vick. You always going to look at it as a competitor. You always going to be out there against the best.”

Polley also spoke about the mental adjustments he made that allowed him to have a successful senior season despite having undergone reconstructive knee surgery and 7 ½ months of rehab in the off-season.

“The mental adjustment is coming off a major knee surgery. Just coming back. Wondering if you can get back. Wondering if you are going to be as fast as you were. My motivation always is I got a family to feed. I got to overcome what we are in right now. That was my main thing. If I come back, I’m already in position…I just got to finish it up.”

Whereas most players who suffer major knee injuries never play at the same level again, Polley returned and had an All-American season. In his final season at FSU, Polley had 100 tackles with 53 solo tackles, 7 tackles for a loss, 2 sacks, broke up 7 passes, and recovered a team-high 3 fumbles and forced one. The defensive leader and captain took the Seminoles to another national championship (2001 Orange Bowl), even though his team ultimately lost 13-2 to the Oklahoma Sooners. He ended his collegiate career with 289 tackles (170 solo) and was a semi-finalist for the Butkus Award, third team Football News All-American, first team All-ACC selection, and a finalist for the ACC’s Brian Piccolo Award (as a result of his courageous comeback from the injury he suffered in the Sugar Bowl).

Polley reflected on making a successful transition from high school to college. He had no fear of playing at the next level due to his previous experience of playing against the elite athletes from Baltimore.

“In Baltimore, when I was growing up, I played with older guys like Donta Bright, Michael Lloyd, and Sam Cassell. I played against guys that were better than me. So when I got to playing guys that were the same age as me, it was a no-brainer. What can these guys do to me, that [the older guys] can’t? Even though football is different, in my mind, it doesn’t matter what level it is. I was playing against pros already. There’s no intimidation factor.”

He offered some helpful advice to high school athletes making the jump to college. In short, keep an open mind and let things unfold.

“First of all be patient. Don’t be scared to redshirt. Because once you get there, you got guys already in line. They might not have told you about that guy that they recruited 2 years ago. Just be patient and buy your time. It’s going to work out for you as long as you do what the coaches ask of you, work hard, and go to class. Just to do all the things that you are supposed to do and do everything the coaches ask you to do because they have been there before. They have already sent guys to the pros and they’ve seen guys not make it.”

He also provided guidance to talented college players, who are NFL-bound, and the tough situations they may face that could jeopardize their eligibility.

“Just be careful. Know the rules. Don’t make things too obvious. Don’t ride around in a slick car with big chains. Don’t do the obvious. It’s going to happen. I can’t tell a 17-year old not to do it. Just be careful, know the rules, and don’t do what everybody else is doing.”

As a former star player, Polley does not cover up the reality of the situation—that many star college athletes take gifts—and implores them to use common sense and follow the rules, not their teammates.

When asked what his best memory was playing under Coach Bobby Bowden, it was not just one thing, but the entire package.

“It is his whole every day approach. His vibe. How he talks to a player. How he talks to the media. His whole vibes. He’s not too arrogant, but he is a good stern coach. He’s funny. Janikowski stayed out late [before the national championship]. People asked him ‘how come you didn’t suspend Janikowski?’ He said, because you got international rules. He couldn’t suspend Janikowski, but he made him do some extra running in practice. He had his own way of dealing with things.”

Polley was especially candid in offering his personal opinion as to why Bobby Bowden continues to coach after 34 seasons. In his view, the driving force is not the competition between Bowden and Penn State’s Joe Paterno over who will finish their career as the all-time leader in Division-I coaching victories. He attributes it to comfort in routine and fear of letting go.

“I think with the old coaches, they don’t want to die. I think Bear Bryant might have died 6 months after he retired. (Editor’s note: In fact, Bryant died of a massive heart attack only 28 days after his last game as a coach.) So most of these guys think if they retire, they got nothing to do and what else is left? They are looking at their predecessors and how they died. I think that is why he is trying to hang around…to hang [on] to his life a little longer.”

Following a spectacular career at FSU, Polley was selected as the 42nd pick in the 2001 NFL Draft. It is every football player’s dream to be drafted and Polley shared his feelings about the process.

“I was excited! Now is my time. I’m here now. I paid my dues. Now it’s time to cash in. Like I said, as a competitor, you always want to play against the top players in the world. As much trash as I talk, I wanted to get a chance to prove that I can play at that level. Since being small, I always wanted to play at the highest level. So, I had a chance to do that. It worked out well.”

For his agent, Polley selected Tom Condon, who headed up IMG’s Football Division at the time (he has since moved on to Creative Artists Agency (CAA)). Because of lingering questions NFL teams had about Polley’s bad knee, he wanted to go with a big-time agent who could erase any doubts about his health. Condon certainly fit that bill. On top of that, Polley was attracted to the overall package, including the free workouts IMG offered. “I might have had to pay for my workouts with another agent,” added Polley.

It is a fact that some colleges have a few preferred agents that the coaching staff recommends to players when they become eligible for the NFL Draft. Polley described the open system that FSU has with respect to the agent process.

“See when you go to FSU, it’s not like USF, where you might have one player come out every 10 years. Every year, you got about 10 players who might get drafted [out of FSU]. So for a coach to point you in a direction, would be wrong. It’s more open. There are some schools out there that have their agents, but Florida State is more open. Anybody can come in and get a player.”

With Condon’s extensive client list, I was curious about the level of personal attention Polley received when he was represented by IMG. This wasn’t a concern of Polley’s at all, at least in the beginning of his career.

“At first, I didn’t want that. At the time it was going on, that part of the process wasn’t as important to me as it was to somebody else. I didn’t care about the personal attention. I didn’t want an agent calling me everyday asking me what I was doing. Just get me the deal basically. I am going to do the work and you are going to get me the deal.”

Later in Polley’s career, it seems as though he would have preferred more attention from his agent with respect to his contractual situation.

“The thing about it is with some agents, sometimes they look out for them[selves] and I don’t know if they look out for the bigger picture. They are just going more for the big dollars, whereas the team may be looking at how things could work out. They didn’t negotiate what I was worth. Maybe they had bigger clients. I don’t know what the whole process was like. Everybody’s situation is different. My situation was a sticky situation. I’m a good player. [My] numbers say that I’m worth this, but [they] aren’t going to give [me] that. I don’t know if my agent was upfront with me about those discussions…I want to take that deal and it’s just laying there and laying there, and now you gotta take this deal. Now, you got a one-year deal and another one-year deal. Maybe some of the offers they were expecting didn’t come in, so I don’t know.”

Polley came across as resentful with respect to how his contract situation was handled toward the end of his career. After 4 seasons with the Rams, he finished his career by spending one-year with the Baltimore Ravens and his final year with the New Orleans Saints. Polley presents an interesting picture of the free agency process, and how at times, some players are seemingly left in the dark by their agent(s) about existing offers that may be on the table for the sake of wrapping up negotiations.

After Polley went unsigned as a free agent in 2007, he retired from the NFL and quickly transformed himself into a businessman. Polley’s first venture involved launching an independent film production company called Big Vision Films, along with two other Dunbar High School alumni, Rob Foster and David Manigault.

Big Vision Films was formed to bring socially conscience ideas to independent films, in an effort to revolutionalize independent film production. Big Vision’s first project is a documentary titled Poet Pride, which sets out to capture the legacy of Dunbar High School’s storied basketball program. There are very few high school teams in the nation, if any, that have dominated on a national level, and accomplished what Dunbar has over the years. Dunbar stands alone with four mythical national championships (#1 ranked team in the nation), winning three titles in the 80's, and one in the 90's.

Poet Pride will chronicle the tradition of Dunbar basketball, from the program’s early days in the 1950s when the players encountered segregation; to the 1982-83 mythical national championship team (widely considered one of the greatest high school squads of all-time); to the mythical championship of the early 90s when Dunbar boasted McDonald’s All Americans year after year in Michael Lloyd (‘92), Donta Bright (‘92), Keith Booth (‘93), and Norman Nolan (‘94).

Polley and company believe that although the Dunbar story is firmly entrenched in the Baltimore social fabric, its universal themes of enduring hardship, turning adversity into triumph, and sports transcending social ills (e.g. racism) appeal to an audience beyond Baltimore.

“I felt like the idea had mass appeal. Poet Pride is just the foundation of everything yet to come. This is going to make people know we are for real.”

The Big Vision crew has been working for nearly a year and nine months on the production. Production costs to this point have totaled around $50,000 and are being financed primarily by Polley. Minigualt, who is a former Dunbar basketball player turned actor and director, is currently working to get the film picked up by a major studio in Los Angeles. The documentary is planned to be about 90 minutes and is tentatively scheduled to be released this summer. Oh, and they are currently looking for a voiceover artist.

Additionally, Polley also co-founded Big Vision Sports LLC (“BVSports”) and The Tommy Polley Foundation. BVSports produces team highlight videos, college recruiting videos, promotional videos for sports organizations, instructional videos, as well as commercials. Polley’s foundation focuses on educating inner-city youth of Baltimore and works with them to develop their life skills through mentoring.

In the little time I spent with Polley, he seems to be handling the transition from professional athlete to businessman quite well. He has big plans. Even better, he has big visions.

On behalf of AccessAthletes, we would like to thank Tommy for taking time out of his busy schedule to do an interview with The Real Athlete Blog. Matthew Allinson can be reached at matt@accessathletes.com.